Understanding the Sciatica

I realize you may not have gotten the pun in “shake a leg”—people who have sciatica often have symptoms down their leg. Some don’t have any back pain at all! This pain is stabbing, burning, shooting, and sharp; it’s been described as “an electric shock going down the leg,” or “like a thousand needles are stabbing into my leg every time I take a step.” Yikes! When people do have back pain, it is typically in the low back, and one-sided. Most people will experience a constant ache with sharp pains with movement. Aside from pain, people tend to experience muscle weakness in the painful areas and end up using compensatory movements that lead to overall lower extremity weakness.

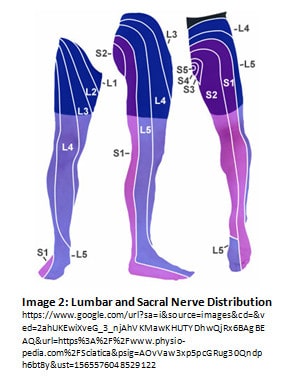

Sciatic symptoms follow a consistent pattern down the leg; typically, from the low back, through the buttocks and rear thigh, around the outside of the knee and calf into the outer edge of the foot. Not everyone has sciatica all the way to the foot; some only have symptoms in the buttocks and thigh, some just in the lower leg. We will discuss why when we talk about the neuroanatomy.

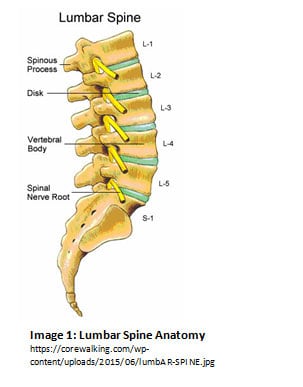

Sciatica is chiefly a nerve irritation, which can be caused by either compressing or tensioning the nerve. The primary causes of compression are disc bulge or herniation, spinal stenosis, spondylosis, and facet dysfunction. Recall the anatomy of the spine (see Image 1): nerve roots exit between vertebrae, which are attached via intervertebral discs. The nerve roots affected in sciatica are those of the sciatic nerve: the roots that exit between vertebra L2-S3. Not all of the roots need to be affected for someone to have sciatic pain. Different nerve roots correspond to different areas of the lower extremity (see Image 2).

Each of the aforementioned common causes of sciatica affects the nerve root in a different way. Discs may bulge or herniate in the direction of the nerve root and compress it. Stenosis is a fancy word for when the bony space that the nerve exits through (called the intervertebral foramen) is narrowed for one reason or another (genetics, poor injury healing, arthritis, etc.).

Spondylosis is another fancy word: it is essentially arthritis of the spine and manifests as a combination of stenosis and facet dysfunction. People with spondylosis also experience spinal stiffness and decreased range of motion. Facet dysfunction refers to when the joints between the vertebra do not glide over one another smoothly or move too much or too little. Facet dysfunction can lead to either compression or tension to the nerve root.

Tension on a nerve often occurs at more peripheral sites. The most common cause of tensioning in athletes is a hamstring or calf strain or injury. The sciatic nerve (and its branches) are in a “neurovascular bundle” containing the nerve, arteries, and veins feeding that particular muscle. That bundle is protected and held together by connective tissue and must be able to slide within the muscle as it is stretched and contracted. Soft tissue injuries that produce scar tissue can create “sticking points” along the track of the neurovascular bundle, which oppose sliding and force the nerve to stretch excessively.

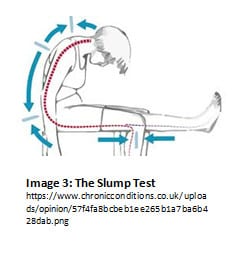

Try this: sitting in a chair, slouch down so that your low back is rounded. Keeping your thigh parallel to the floor, extend one knee, and flex the foot of the same leg (bring your toes up toward your knee) (see Image 3). Feel a little zing into your foot? Or maybe you’re unable to straighten your knee all the way? Congratulations, you’ve experienced what it’s like to tension a nerve! [Note: feeling tension with this exercise is not pathological; we’ve simply put you in a position that provides tension to both ends of the nerve.]

Deep Dive: Nerve Irritation

Let’s quickly discuss what “nerve irritation” looks like physiologically. After the nerve root comes out of the intervertebral foramen, it splits off into several branches, leading to different areas of the body. These nerves are two-way: they can both transmit messages from the brain to the muscle, as well as messages from the muscle to the brain. The messages to the muscle are motor messages (contracting and relaxing), and the messages from the muscle is sensory in nature (muscle length, tension, pain, etc.). [This is an over-simplification, but let’s not get into all of the different types of nerves and how they work…that’s a topic for another day.]

When a nerve is “irritated,” the nerve is experiencing some sort of chemical or a mechanical stimulus that disrupts its typical function of transmitting those motor messages in a way that the muscle can respond appropriately. It may send too many stimuli too quickly, causing spasms or cramping or it may not be sending enough stimuli, causing weakness due to a reduced number of muscle fibers contracting. The sensory response from the muscle is often also compromised, and the brain interprets that signal as pain. With irritation at a site other than the nerve root, the messages being sent essentially hit a “speed bump,” although the messages may be slowed or accelerated.

Treatment and Prevention

Luckily for people with sciatica, it is treatable. Not only is it treatable, but the treatment does not need to involve intensive surgery or implanted medicinal delivery devices. There are several research studies that have found that most people who have the structural issues that compress the sciatic nerve can live pain-free even if their imaging shows a disc bulge or spondylosis. For these more centrally-sourced cases of sciatica, a physical therapist or chiropractor can treat it at the source: the spine. For peripheral sciatic pain caused by soft tissue injury, a physician or physical therapist would be preferred providers. Rehabilitation of sciatica is different for every patient depending on the cause, irritability of symptoms, and the person as a whole. Most regimens involve mobility training, strengthening, and cardiovascular exercise.

Mobility focuses on both how the nerve moves through the muscle and how individual joints move together and independently. This training allows the nerve to slide more smoothly through the muscle bellies that it is in, while also providing functional tensioning and compressing with typical movement. It is important to also strengthen the muscles that both influence the tension/compression on the nerve and the muscles that are influenced by the nerve irritation. Strength training is an indirect way of regulating nerve impulses. By working at the muscle, signals sent from the muscle can provide a calming effect on the nerve and “train” the nerve to fire appropriately.

Cardiovascular exercise is also very important, as it keeps oxygen and other nutrients circulating around the body and removes wastes. There are microscopic blood vessels that nourish our nerves and help remove any waste materials that build up. Having a healthy cardiovascular system is paramount to maintaining normal function of our nerves.

The ways of preventing sciatica are the same as treating it: stay mobile, stay strong, and take care of your heart. A quick note about mobility exercises: mobility and flexibility are similar, but I chose the word “mobility” intentionally. When most people think of flexibility, they think of performing splits and long sustained stretching. Sustained stretching can actually cause undue excessive tensioning of the nerve, so I encourage mobility exercises as a way of developing flexibility through continuous full-range movements. These movements are more specific to the sliding that occurs with that neurovascular sheath and can better prepare you for functional movements that you use every day.

So, there you have it; the [abbreviated] summary of sciatica. If you think that you may have sciatic nerve pathology, contact your physician or stop by a physical therapy office. They can screen out any potential red flags and get you on track for rehabilitation. If you have concerns about developing sciatica, I highly encourage looking into mobility exercises (#mobilityWOD, among others), and decreasing the amount of sustained stretching performed on the lower extremities and back. Our bodies are amazing at regenerating and repairing; so don’t be nervous and get moving!

Sources:

- Boxem KV, Cheng J, Patijn J, et al. 11. Lumbosacral Radicular Pain. Pain Practice. 2010;10(4):339-358. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00370.x.

- Delitto A, George SZ, Dillen LV, Whitman JM, et al. Low Back Pain: Clinical Guidelines. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(4):A1-A57

- Tarulli AW, Raynor EM. Lumbosacral Radiculopathy. Neurol Clin. 2007;25(2):387-405

- Rydevik B, Brown MD, Lundborg G. Pathoanatomy and pathophysiology of nerve root compression. Spine. 1984;9(1):7-15.

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Sciatica