Knee Ligamentous Injuries

The knee joint is possibly one of the most complex and interesting joints of the human body. For most of us, they are the structure that gets bumped the most on chairs, coffee tables, or medium to large-sized dogs. Those minor traumas aside, we will discuss injuries of the knee below the surface—i.e. within the joint. Most of us have heard of these injuries: ACL tears, MCL tears, meniscal tears, patellofemoral pain syndrome. We have heard of them because they are among the most common injuries suffered by athletes—both elite and amateur. We will talk a bit about why that is, the causes of these injuries, their rehabilitation and prevention. Ready or not….

Anatomy Overview

On a macro-anatomy level, the knee can be considered a “sandwich” joint: it hangs out between the hip joint and the ankle joint, and to a certain degree is at their mercy. For example, a person with a history of ankle sprains will likely have residual instability in that ankle. However, the body learns to compensate by transferring the load up the chain to the knee. The same thing happens with the hip. A hip injury or muscle weakness (let’s just say, osteoarthritis of the hip) will cause a compensation that passes the load down the chain to the knee. See what I mean? Sandwiched.

All of that aside, let’s talk about how the knee attaches. There are actually TWO joints that make up the knee: the tibiofemoral (the thigh bone is connected to the shin bone), and the patellofemoral (the kneecap is connected to the thigh bone). (I hope you all sang that with me). For the sake of this article I will talk more about the tibiofemoral joint, as it is the larger of the two and the most commonly impacted by injury.

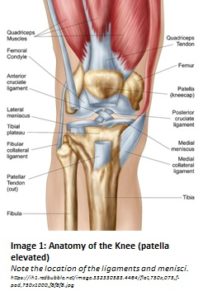

When we look at the bottom of the femur (thigh bone) and the top of the tibia (shin bone), we notice that there is a lack of bony congruency. This means that the femur does not just sit on top of the tibia like a perfectly placed puzzle piece; it has a little help. The menisci (there are two) cover the top of the tibia and create little basins for the round parts (condyles) of the femur to sit in and glide on during movement. You can think of it like a dense cushion that is perfectly molded to the shape of the femur. Because we would like our knees to bend in order to accomplish myriad activities, the menisci cannot be fused to the femur the way that they are to the tibia: enter, ligamentous support.

When we look at the bottom of the femur (thigh bone) and the top of the tibia (shin bone), we notice that there is a lack of bony congruency. This means that the femur does not just sit on top of the tibia like a perfectly placed puzzle piece; it has a little help. The menisci (there are two) cover the top of the tibia and create little basins for the round parts (condyles) of the femur to sit in and glide on during movement. You can think of it like a dense cushion that is perfectly molded to the shape of the femur. Because we would like our knees to bend in order to accomplish myriad activities, the menisci cannot be fused to the femur the way that they are to the tibia: enter, ligamentous support.

Ligaments are bands of dense, non-contractile connective tissue that provide stabilization to joints by regulating the amount of excessive movement that occurs. They exist to protect our joints while still allowing the dynamic movement that allows us to accomplish everyday tasks.

In the knee, there are four primary ligaments that provide this “check” to ensure that the joint moves within its feasible ranges. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (ACL, PCL), and the medial and lateral collateral ligaments (MCL, LCL) work together to provide support in all directions (see Image 1).These are the main structures we will discuss regarding injury.

Common Ligamentous Injuries

The ACL and PCL are in the center of the joint and make an X-shape. These ligaments become taut when the knee is flexed to prevent unwanted motion from multidirectional forces.  Seventy percent of ACL injuries are non-contact in nature. They occur during a plant and twist motion, typically in conjunction with a rapid deceleration. We see this a lot in soccer and football players: they’re running down the field, gaining speed, and suddenly slow down and change direction to avoid an opponent or obtain the ball. Just like that, they end up on the ground writhing in pain.

Seventy percent of ACL injuries are non-contact in nature. They occur during a plant and twist motion, typically in conjunction with a rapid deceleration. We see this a lot in soccer and football players: they’re running down the field, gaining speed, and suddenly slow down and change direction to avoid an opponent or obtain the ball. Just like that, they end up on the ground writhing in pain.

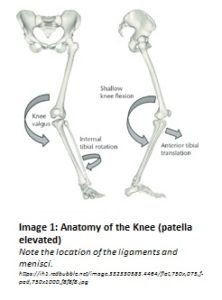

The ACL tears when the knee experiences excessive combined internal rotation and valgus forces (see Image 2). A valgus force is a force that causes the knee to move inward while the hip and ankle remain outside of it. The knee is most vulnerable to injury in this position when it is in a slightly bent position, such as when one initially loads weight onto their leg.

PCL injuries are relatively rare based on the anatomy of the ligament and typical movement patterns of the knee. They occur by a force that sends the tibia backward; some may have heard of a “dashboard injury,” when the dashboard of a car slams into one’s shins. Another mechanism is hyperextension of the knee. This is extremely rare, as a tremendous amount of force is required to overcome the muscular and bony defenses against hyperextension and rupture the ligament.

The MCL and LCL are on either side of the knee joint, attaching from the femur to the tibia. They are responsible for making sure the knee moves forward and backward—not side to side. The MCL and LCL can be injured in conjunction with an ACL or PCL injury, or can be injured on their own via a direct force inward or outward on the knee. The MCL is more commonly injured than the LCL, due to its vulnerability as both a smaller ligament and based on the types of forces humans habitually receive on their knees. Athletes are at high risk of injuring these ligaments during contact events, such as a slide tackle.

The Unhappy Triad

It is important to talk about the “unhappy triad,” as it is a regularly seen pattern of injuries. The unhappy triad includes an ACL sprain, an MCL sprain, and a meniscal tear. The mechanism of injury is typically similar to that of an ACL injury, a plant and twist, with increased compression and valgus forces. The quality of an individual’s tissue and the force of the injury determine which structures will be compromised and how badly.

A Note Regarding the Meniscus

As it was mentioned in the unhappy triad, I cannot resist sharing just a tidbit about the menisci. As stated in the anatomy section, the menisci make the tibia congruent with the end shape of the femur. A meniscus tears typically due to an excessive shear force, one that compresses and slides perpendicular to the surface of the tissue.  There are three types of meniscal tears: longitudinal, radial, and horizontal (see Image 3). Longitudinal tears are along the striations of the tissue. The right hand column of the image shows potential futures for smaller tears, however, the bucket handle tear shown may occur at the time of the initial incident, depending on the force involved. Radial tears begin in the center of the meniscal “basin” and tear outward. These tears may be difficult to heal based on how close together the edges of the tear are. Horizontal tears have at least one portion that is perpendicular to the tissue striations.

There are three types of meniscal tears: longitudinal, radial, and horizontal (see Image 3). Longitudinal tears are along the striations of the tissue. The right hand column of the image shows potential futures for smaller tears, however, the bucket handle tear shown may occur at the time of the initial incident, depending on the force involved. Radial tears begin in the center of the meniscal “basin” and tear outward. These tears may be difficult to heal based on how close together the edges of the tear are. Horizontal tears have at least one portion that is perpendicular to the tissue striations.

The primary determinant of whether or not a meniscal tear will heal on its own is its location. Tears in the outer third of the meniscus receive better blood flow and have a higher potential of healing on their own. Larger or more internal tears may require surgery.

Options Post-Injury

In the unfortunate event that you or someone you know experiences a ligamentous sprain one (or several) knee ligaments, there are a number of options. Obviously, a primary care provider should assess the situation. The grade of the sprain will ultimately determine the next steps. Grade I sprains are an over-stretching of the ligament causing inflammation; often there is only micro-tearing at the site. Grade II sprains tear through part of the ligament, but not all of it. The sprains can be resolved on their own or by surgical approximation depending on severity and other patient factors.

Grade III sprains are the ones that are top of mind: the full ruptures. In this grade of sprain, the ligament has been torn all the way through. Depending on which ligament it is, there may be options to repair, replace, or seek conservative treatment. Repairs and replacements involve surgical procedures to recover the integrity and function of the ligament. Conservative treatment usually consists of some sort of physical therapy to train the muscles around the joint to compensate for the missing ligamentous structure. It may seem odd to no seek a repair or replacement, however there are many people walking around without ACLs today. The decision of how to proceed is based on a person’s health status, age, and goals/use of the joint.

Prevention

The easiest way to deal with a ligamentous knee injury is to not have one in the first place. Athletes, recreational or elite, would tremendously benefit from a regular exercise regimen that includes mobility and agility training. Mobility training focuses on how joints move and stabilize together to produce full range movements. Agility training is a combination of power and balance. It trains quickness and reaction time, both for voluntary movement and subconscious stabilization. If you have ever watched a sports practice (or participated in one), there are typically drills involving stopping and starting, cutting, and reacting. These drills are extremely important to train our bodies for how to respond to those unpredictable game-day situations.

A lot has been covered in this article: ACLs, PCLs, MCLs, menisci. The bottom line is this: knee ligamentous injuries typically occur from stereotypical movement patterns with extreme forces. There are so many structures in the knee promoting its stability; while ligaments are an integral part, structures like the menisci and the surrounding soft tissue ensure that knees stay in line (literally and figuratively). Ligaments do get stronger with training; as do the neural connections between our brains and every element of our joints. Strong neural connections mean that the messages to turn on and off muscles and react to new stimuli run quickly and efficiently, helping your body function optimally. Work hard, work smart, and remember: you’re the bee’s knees!

Sources:

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Knee

- Knee Ligament Sprain Guidelines: Revision 2017: Using the Evidence to Guide Physical Therapist Practice.J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.2017 Nov;47(11):822-823. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.0510.

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Anterior_Cruciate_Ligament_(ACL)_Injury

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Medial_Collateral_Ligament_Injury_of_the_Knee

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Lateral_Collateral_Ligament_Injury_of_the_Knee

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Posterior_Cruciate_Ligament_Injury

IMAGES:

- https://ih1.redbubble.net/image.332330583.4464/flat,750x,075,f-pad,750×1000,f8f8f8.jpg

- https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ata_Kiapour/publication/260108175/figure/fig1/AS:392654375407619@1470627506941/Schematic-showing-the-multi-planar-loading-mechanism-of-non-contact-injury-to-the.png

- https://www.limbreconstructions.com/uploads/5/4/6/1/54615109/2536836_orig.png