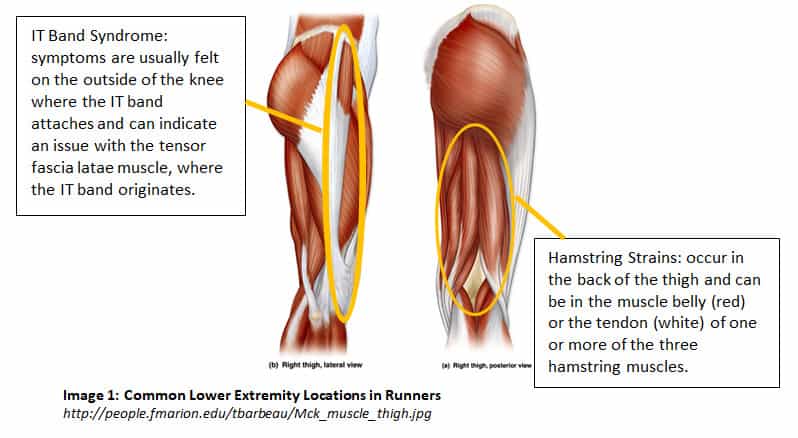

Common Injuries in Runners: Hamstring Strains + IT Band Syndrome

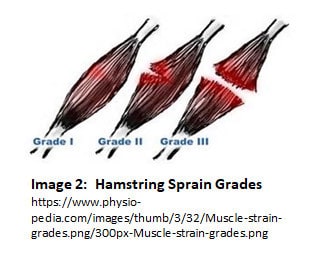

Hamstring strains are the most common lower extremity injury in athletes, and typically occur in sprinters (as opposed to long distance runners). The hamstrings are located on the back of the thigh and are composed of three muscles: biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus. Strains can occur in any muscle and are graded I-III depending on severity (see Image 2). A grade I tear is characterized by damage to 10% or less of the muscle and is painful with no loss of function or weakness. Grade II tears involve disruption of 10-15% of the muscle and are both painful and cause weakness, although a person with this grade strain can still use the muscle. Grade III tears are the most severe, with 50% or more of the muscle being disrupted, and the person with this strain experiencing pain, weakness, and loss of function of the muscle.

Causes

So, what causes a hamstring strain? There are two mechanisms: 1) repeated excessive stress on the muscle with inadequate rest causing muscle tissue damage, and 2) a single event of maximal eccentric force that is surpasses the mechanical limits of the muscle. The repeated stress mechanism can be explained by typical muscle physiology. Every time a muscle is exercised, there is microdamage to the muscle fibers. Usually, this is a good thing; the microdamage signals the body to repair and grow/strengthen the muscle. A strain is possible when the body does not have enough time between bouts of exercise to repair the area. The repetitive microdamage to the same muscle leads to more muscle breakdown than building, and the muscle becomes painful and possibly weaker.

There were a lot of big words in the second mechanism, so let’s break it down. Our second mechanism is a single traumatic event; it happens in one moment. Eccentric muscle contraction is controlled lengthening of a muscle. In the hamstring, eccentric forces are placed on the muscle at the end of swing phase: the hamstring controls knee extension (straightening) before you put your foot on the ground to take a step. It is during this phase of running that the greatest eccentric force is placed on the muscle. The faster the speed, the greater the force. A strain occurs when the eccentric force placed on the muscle is too much for it to handle. When this happens, the muscle tries to contract (shorten) to protect itself, and the opposing forces cause the muscle to tear.

Risk Factors

There are some predisposing factors to hamstring strains, including insufficient warm up, decreased core strength, and muscular imbalance between the quadriceps and hamstrings. Warming up is extremely important before any athletic activity. Cold muscles are more easily torn due to stiffness; warming up with a light jog or brisk walk or mobility exercises can help with muscle function during exercise. When the core is weak, other areas of the body make up for it–especially the hip musculature. Both the hamstrings and quadriceps attach on the pelvic bone and can be used to compensate for a lack of stability in the core. This compensation is achieved by those muscles contracting more frequently and becoming tight over time. Sometimes the quadriceps and hamstrings have a strength imbalance, which means that one is stronger than the other. Because these two muscles perform opposing actions (quadriceps do hip flexion and knee extension, hamstrings do hip extension and knee flexion), one must lengthen when the other contracts. A person with stronger and tighter quadriceps is at higher risk for a hamstring strain because a powerful quadriceps contraction could contribute to the super-maximal eccentric force placed on the hamstrings. Utilizing a strengthening program that adequately loads both muscle groups is a great way to prevent this risk factor.

We will get into some other prevention and rehabilitation techniques for hamstring strains and IT band syndrome after both have been discussed. Let’s get into IT band syndrome!

IT Band Syndrome

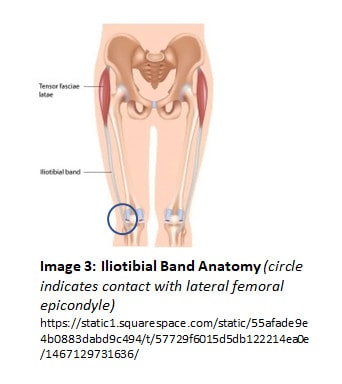

IT band syndrome is the most common cause of lateral (outside) knee pain in runners. We briefly touched on the IT band in the introduction, but let’s talk more about what it is and what it does. The iliotibial (IT) band is a thick band of fascia (connective tissue) that originates from the tensor fascia latae muscle and attaches on the lateral tibia (the outside of your shin bone, just below the knee). The tensor fascia latae (TFL) is located on the front of your hip. You can find it by locating the pointy bones on the front of your hip and then moving your fingers down and slightly outward. That muscle bulk should become firm when you turn your foot inward. The TFL and IT band are related in that when the TFL is tight, it puts tension on the IT

band. This is important because the IT band is not a contractile tissue; it does not shorten or lengthen in and of itself, and has limited elastic qualities. Keep this in mind as we move forward. The TFL does a number of actions at the hip, and the IT band works to stabilize the lateral knee. When the knee flexes and extends, the IT band rubs over the lateral structures of the knee joint, namely, the lateral femoral epicondyle and the top part of the tibia (see Image 3).

Causes

Now that you know more than you ever thought you would about the IT band, let’s get into why it starts hurting. During running, the TFL functions at the hip with internal rotation, flexion, and abduction (kicking your leg out to the side). The shortening of the TFL puts tension on the IT band. Between the IT band and the lateral femoral epicondyle is a layer of fat and a bundle of nerves, arteries, and veins. With repeated knee flexion and extension (as seen in running), the rubbing of the IT band over those structures causes irritation. If the rubbing of the IT band always happens during running, why doesn’t this pain occur in everyone who runs?

Risk Factors

There are a number of structural and functional reasons why IT band syndrome occurs in some people and not in others. Structural causes are not able to be changed through rehabilitation, such as bony anatomy. The major structural risk factor for developing IT band syndrome is an externally rotated femur (in some people it shows up as toe-ing out). Basically, the thigh bone is rotated so that the IT band comes in contact with a greater area of the femur and is therefore put on more tension. More women are susceptible to this based on their pelvic anatomy and the angle of the hip joint, however it may also be seen in men.

Functional risk factors can be modified, typically through stretching or strengthening of the surrounding muscle(s). Examples of these are quadriceps/hamstring imbalances, excessive strength of inner thigh muscles, or abnormal foot/ankle mechanics during running. We discussed quadriceps/hamstring imbalances with hamstring strains above, so I’ll explain the other two a little more. The inner thigh muscles work to bring your legs together, an action called adduction. If these muscles are overactive, they cause an extra internal rotation and inward force on the femur, which tensions the IT band. The ankle and foot relate to knee pain in that any abnormal motion there is compensated for at the hip and/or knee. For example, if a runner has trouble clearing their foot, they are likely to compensate with greater knee and hip flexion to avoid tripping. The extra work given to the knee and hip places greater stress on both the TFL and the IT band, predisposing the runner to IT band syndrome.

Prevention and Rehabilitation

As stated previously, the best way to prevent injuries is to provide the muscle(s) of interest with an adequate warm up and cool down. Preparing the muscle for training or sport is equally as important as performance. A proper cool down and recovery allows the involved tissues to repair and become stronger over time. Along with good practice habits, an appropriate, progressive strengthening program is beneficial to any and all athletes. Intentional strengthening of muscles can reduce imbalances and promote more efficient use of energy systems by the muscle.

Including mobility exercises in your training regimen will contribute to smooth joint and nerve movement during activity. If a joint is limiting motion, the muscle may not be able to work in an optimal range, putting it at risk for injury. Nerves travel in bundles through muscles, and slide within a sheath during movement. Nerve compression from tight muscles can perpetuate muscle pain and tightness, so moving through complete ranges of motion can keep those nerves gliding smoothly.

One more caveat when it comes to core strengthening: we discussed how important it is for the core to stabilize in order for the hip musculature to function as intended and avoid compensation. Remember to also practice spinal mobility. All nerves to the extremities originate at the spine, and if your spine is not moving well, you are more likely to have problems there that could refer down into the limbs.

If you or someone you know experiences one of these injuries, set up an appointment with a physical therapist. With conservative treatment, most people with hamstring injuries can return to play in 16-50 weeks (depending on severity), and people with IT band syndrome can return to play in 6-8 weeks. For the best injury prevention, stay strong, stay mobile, and recover well. For the best rehab, reach out to a professional to discuss a treatment and a progressive program to return to your activity.

Sources:

- Hamstring strain. In DynaMed Plus [database online]. EBSCO Information Services. http://www.dynamed.com/login.aspx?direct=true&site=DynaMed&id=116919. Updated March 30, 2018. Accessed September 2, 2018.

- Hamstring strain. Physiopedia website https://www.physio-pedia.com/index.php?title=Hamstring_Strain&oldid=197355. Updated August 30, 2018. Accessed September 2, 2018.

- Iliotibial Band Syndrome. Dynamed. http://www.dynamed.com.proxygw.wrlc.org/topics/dmp~AN~T116225/Iliotibial-band-ITB-syndrome#Overview-and-Recommendations. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Iliotibial Band Syndrome. Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Iliotibial_Band_Syndrome. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Saika S, Tepe R. Etiology, Treatment and Prevention of ITB Syndrome: A Literature Review. Topics in Integrative Healthcare. 2013; 4(3). http://www.tihcij.com/Articles/Etiology-Treatment-and-Prevention-of-ITB-Syndrome-A-Literature-Review.aspx?id=0000406. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Iliotibial Band Syndrome. Clinical Key. https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/clinical_overview/67-s2.0-44925320-1d10-452e-a169-42bb30de0c36. Accessed August 28, 2018.